Introduction

I stepped upon an interesting paper: Exact Combinatorial Optimization with Graph Convolutional Neural Networks a while ago. In this work, the authors provided a novel methodology for solving mixed integer linear programming with the help of machine learning leveraging the insight of speeding up only a specific part of the exact algorithm might preserve exactness.1

This idea is interesting enough, so I decided to implement it and turn it into a small project. I focused on a specific, well-known TCS problem: the traveling salesman problem, also known as TSP.

Preliminary

We will utilize GCNN (Graph Convolutional Neural Network), a particular kind of GNN, together with imitation learning to solve TSP. In particular, we focus on the generalization ability of models trained on small-sized problem instances.

Integer Linear Programming Formulation of TSP

We first formulate TSP in terms of integer linear programming.2 Given an undirected weighted group , we label the nodes with numbers and define

where is a variable which can be viewed as a compact representation of all variables , . Furthermore, we denote the weight on edge by , then for a particular TSP problem instance, we can formulate the problem as

given by Miller-Tucker-Zemlin.

Branch and Bound

We then solve TSP as the above ILP formulation by branch and bound. It's possible to do branch and bound sufficiently by choosing a good branch strategy, and since branching and bound involves performing a series of branching strategies, we model this as Markov Decision Process (MDP) in its nature.

Now, our goal is clear: We want to learn from an expert (in this case, a SOTA modern solver ), which is typically called imitating learning.

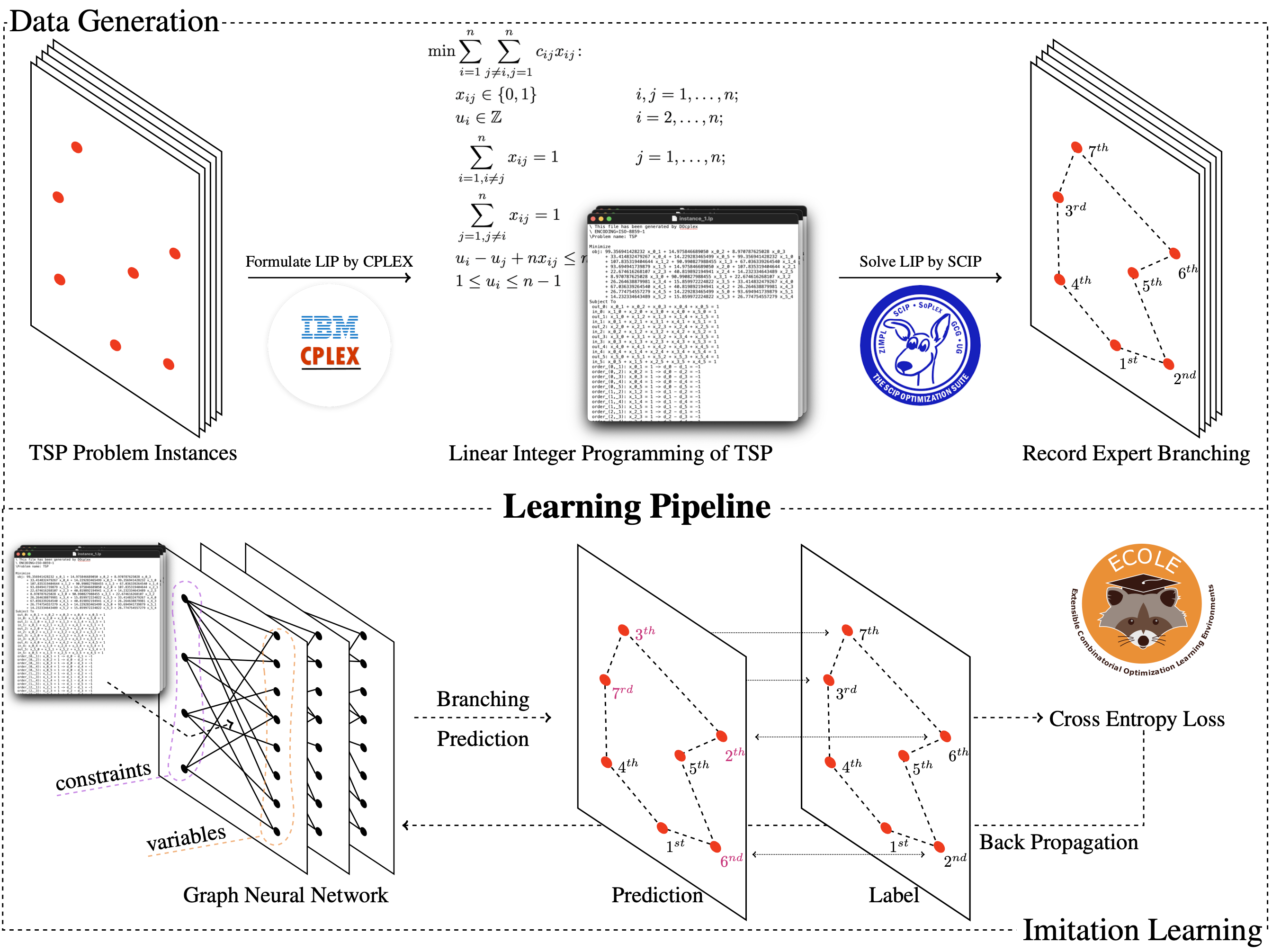

Pipeline

Our learning pipeline is as follows. We first create some random TSP instances and turn them into ILP, then we use imitation learning to learn how to choose the branching target at each branching. Our GNN model produces a set of actions with the probability corresponding to each possible action (in our case, which variable to branch). We then use Cross-Entropy Loss to compare our prediction to the result produced by and complete one iteration.

Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN)

One may wonder where the GNN is involved in our methodology, is it used to model the topology of the nodes of a particular TSP instance?

The answer is no. The GCNN is our model which learns how to perform branching given the state of the problem (e.g., given the current state of the explored recursion tree of the branch and bound algorithm). Intuitively, in the pipeline graph above,

- Top-left corresponds to TSP instances (red dots corresponding to actual cities in the TSP problem).

- Bottom-left corresponds to our model (black dots corresponding to a node in our GCNN).

Now, it should be clear how we utilize GNN to help us solve this TSP problem: We use GCNN to learn a strong branching strategy and use it to do branching whenever needed.

Experimental Result

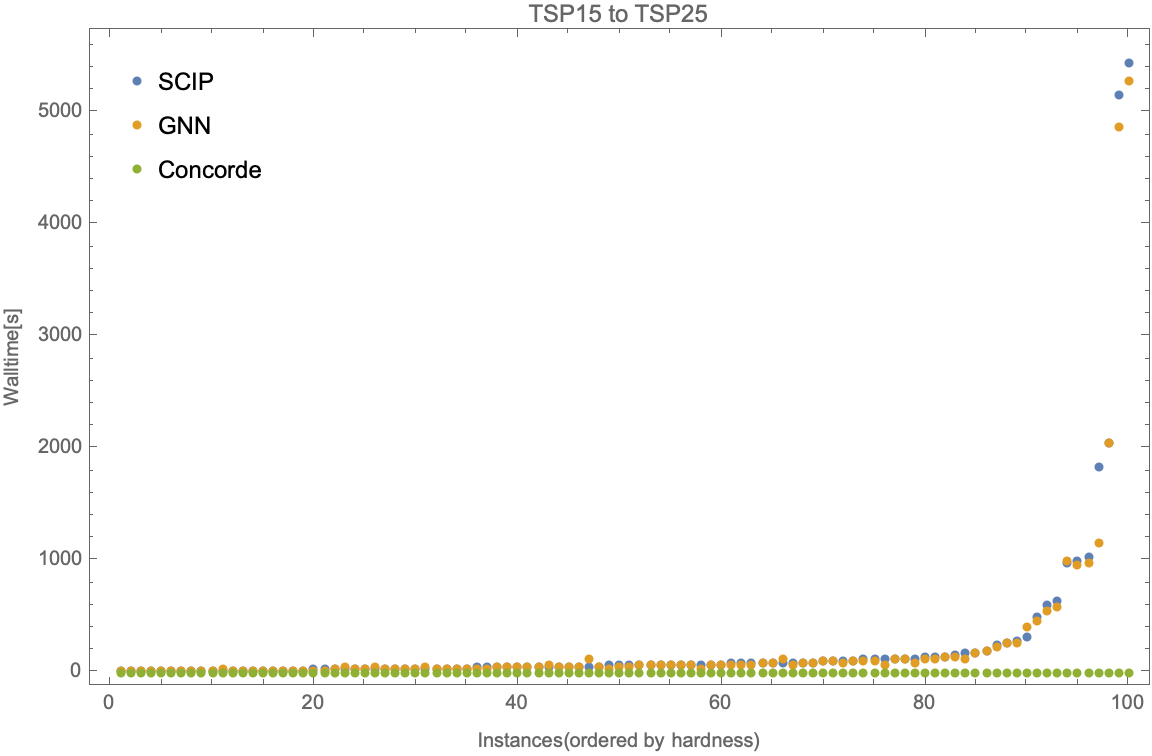

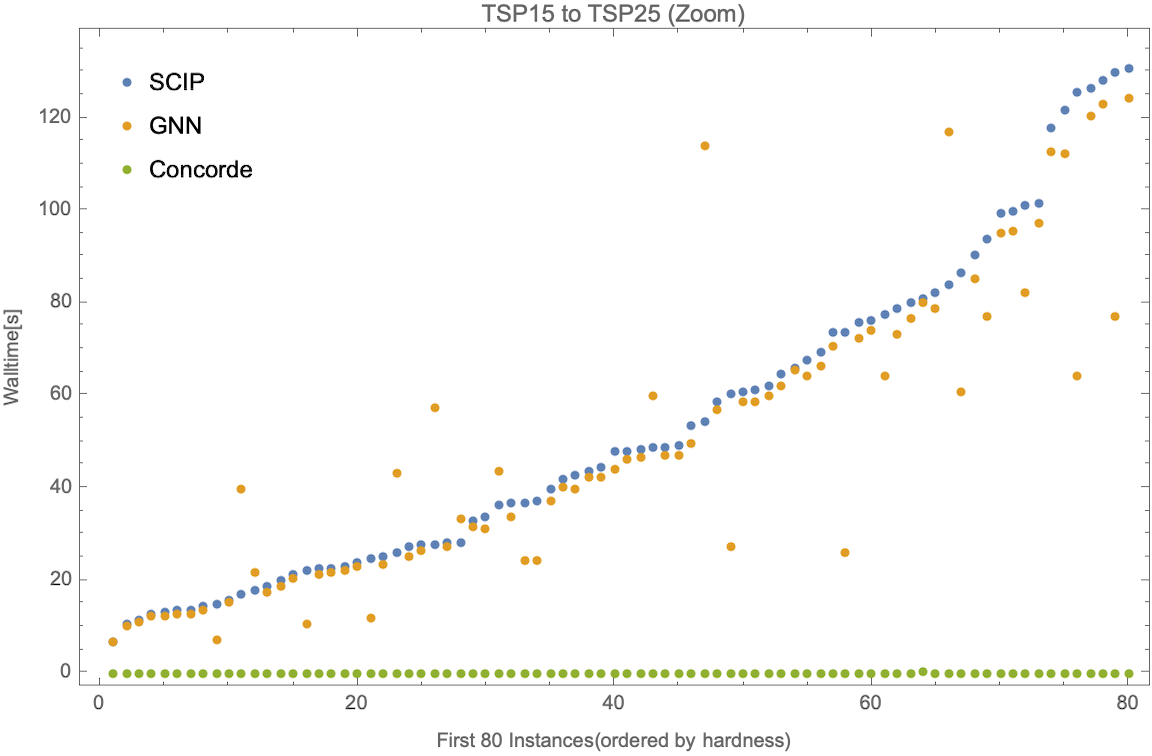

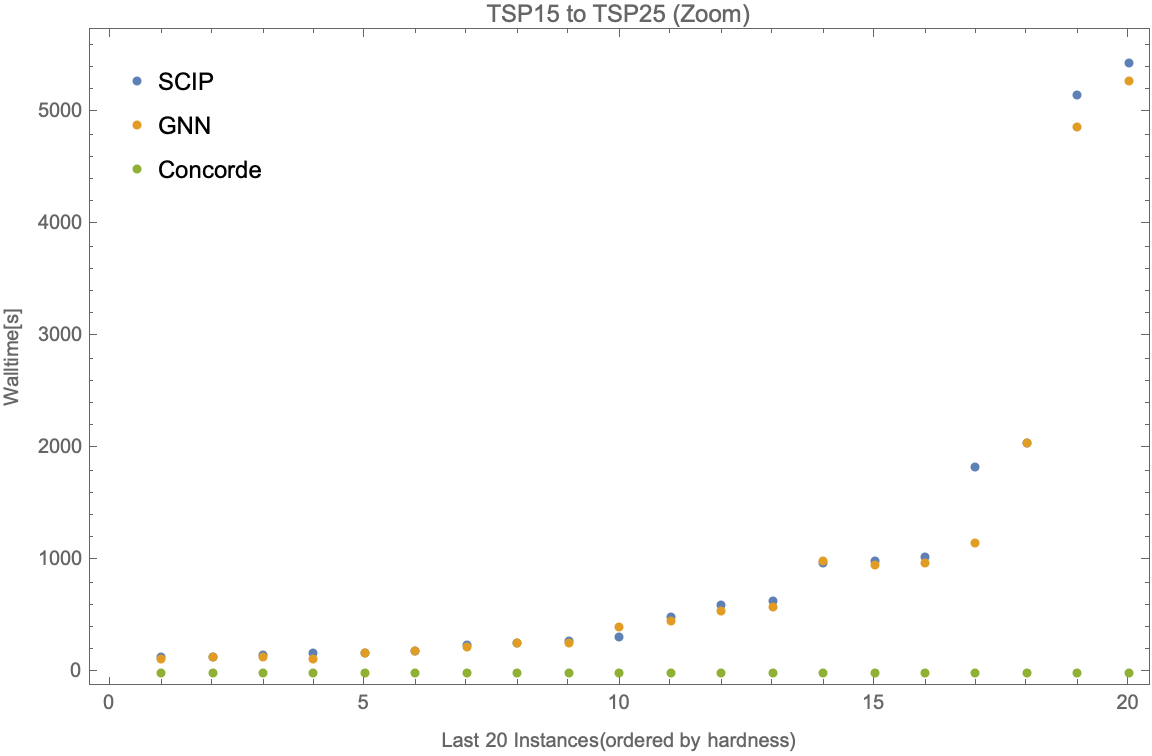

We look at the walltime needed for the model trained on TSP10/TSP15 and tested on TSP25 for 100 instances (ordered by the walltime of ).

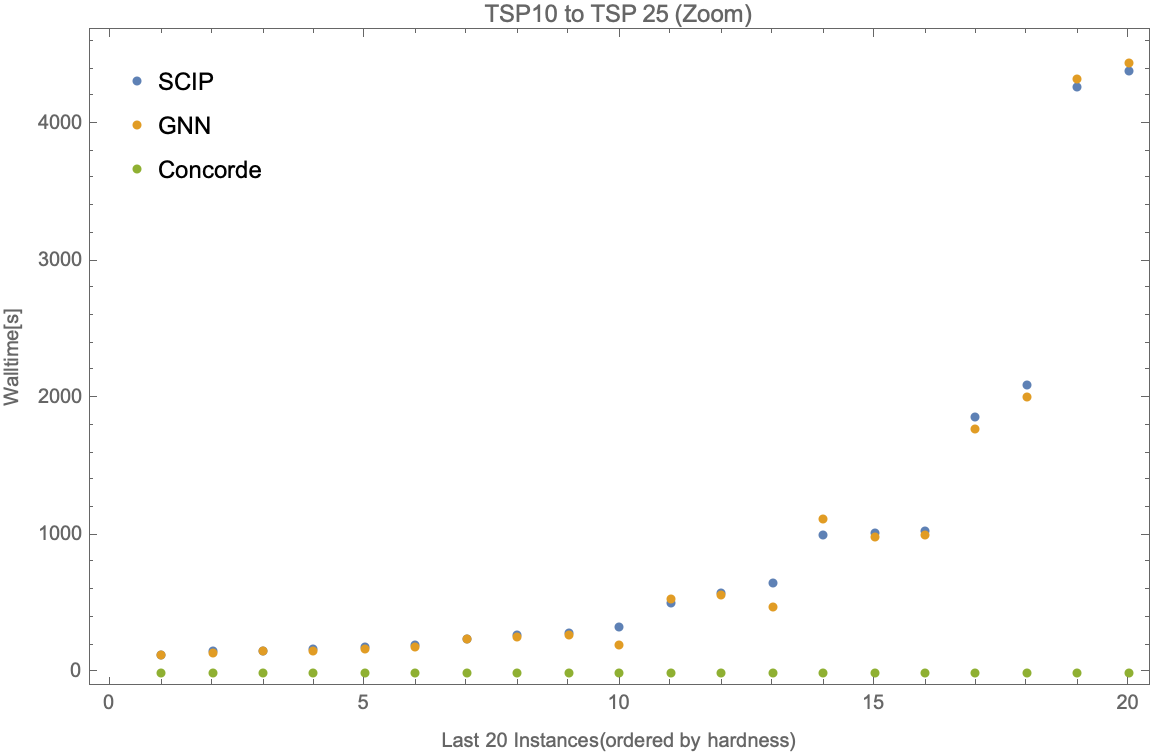

If we zoom in to the first 80 and last 20 instances, we have the following.

Generalization Ability

We observe that our TSP10 and TSP15 imitation models outperform the solver on baseline test instances, and successfully generalize to TSP15, TSP20, and TSP25. They perform significantly better on average than in difficult-to-solve TSPs as compared to easier instances. They also perform better in cases of larger test instances like TSP20 and TSP25 as compared to TSP10 and TSP15. This might be due to an inherent subset structure between TSP10 and TSP20 instances, and similarly, TSP15 and TSP25 instances which might not be the case for smaller test sizes.3

Bottlenecks and Future Work

There is a huge performance difference between our proposed model (also ) and the SOTA TSP solver, . Since the proposed model's backbone is the branch and bound algorithm, by formulating TSP into an ILP, we lost some useful problem structures that can be further exploited by algorithms used in . But the existence of a similar pattern of growth in solving time for more difficult instances of larger TSP sizes even for and is promising, as our imitation model applied to these solvers should lead to similar time improvements.4

Conclusion

For nearly all exact optimization solving algorithms, there is some kind of exhaustion going on, which usually involves decision-making when executing the algorithm.

For example, the cutting plane algorithm also involves decision-making on variables when it needs to choose a variable to cut.

Hence, it's possible to generalize this methodology to not only the branch and bound algorithm but a wide range of the existing exact optimization algorithms.

- There are a bunch of similar works out there trying to achieve this, however, by the nature of machine learning algorithms, all of them fail to provide an exact solution.↩

- The formation detail is omitted here.↩

- Unlike other problems, when we formulate TSP as an ILP, the problem size is growing quadratically. In other words, when we look at the model performance, the generalization ability from TSP10 to TSP25 is not a , but rather a generalization in our formulation. By adapting this methodology to a more sophisticated algorithm that formulates TSP linearly, the generalization ability should remain, and the performance will be even better in terms of TSP sizes.↩

- A major bottleneck is that SOTA solvers like , or , are often licensed, hence not open-sourced. This results in the difficulty of utilizing a stronger baseline and learning from which to get further improvement.↩